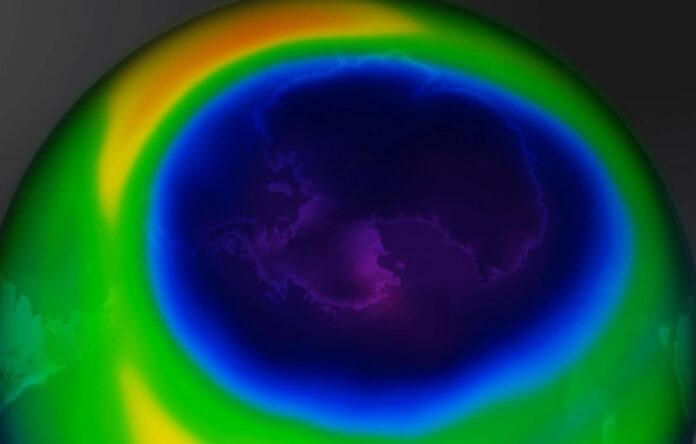

Ozone hole is expanding this year but is still generally becoming smaller.

The Antarctic ozone hole last week crested at a reasonably significant size for the third consecutive year, larger than the size of North America. However, experts note that despite recent blips caused by high altitude cold weather, the Antarctic ozone hole is still usually reducing.

On October 5, the ozone hole reached its greatest size since 2015, measuring more than 10 million square miles (26.4 million square kilometres). According to scientists, conditions are ideal for ozone-eating chlorine compounds because of cooler than usual temperatures above the southern polar regions at a height of 7 to 12 miles (12 to 20 kilometres), where the ozone hole is. “The general tendency is upward. According to Paul Newman, chief earth scientist at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, who monitors ozone depletion, “It’s a little worse this year because it was a little colder this year. “All the evidence indicates that ozone is recovering.”

According to senior ozone researcher Susan Solomon of MIT, simply examining the extent of the greatest ozone hole can be misleading, particularly around October.

The most important month to consider ozone recovery is September, not October, according to Solomon, who said in an email on Thursday that “ozone depletion starts LATER, takes LONGER to get to the maximum hole, and the holes are often smaller. High in the atmosphere, pollutants like chlorine and bromine eat away at the ozone layer that shields the Earth. According to Newman, cold weather produces clouds that release the compounds. The ozone hole grows in size with increasing cold and cloud cover.

According to climate change theory, heat-trapping carbon from the burning of coal, oil, and natural gas warms the Earth’s surface while cooling the upper stratosphere above it, according to Newman. He added that the ozone hole is, however, a little lower than the area that is believed to be cooled by climate change. Research and other experts do link local cooling to climate change.

Climate change-related stratospheric cooling is a problem, according to atmospheric scientist Martyn Chipperfield of the University of Leeds. The concern is that efforts to close the ozone hole and combat climate change may become entangled.

When atmospheric chemists first discovered the increase in chlorine and bromine in the atmosphere decades ago, they issued dire warnings about catastrophic crop losses, food shortages, and sharp spikes in skin cancer if nothing was done. The Montreal Protocol, a historic agreement signed in 1987 that forbade ozone-depleting chemicals, is frequently regarded as an environmental success story.

It takes a long time since one of the main compounds that destroy ozone, CFC11, can linger in the atmosphere for decades, according to Newman. Additionally, research indicates that CFC11 levels in the air were increasing a few years ago, and scientists suspected companies in China for this increase. According to Newman, chlorine levels have decreased by roughly 30% since their peak 20 years ago. It would have been a much, much greater crater than it is currently if these low temperatures and chlorine levels from 2000 had transpired.

Solomon deemed the ozone hole’s third consecutive year of peaking at more than 9.5 million square miles (24.8 million square kilometres) to be extremely rare and deserving of further research.

Brian Toon of the University of Colorado mentions the enormous fires in Australia and the massive water injection from the underwater volcano eruption in January as recent phenomena that might be having an effect.